JULY 2016

Ben Gardane, TUNISIA –Mabrouk Muaffak gazes at a photograph of his daughter Sarah as he leafs through drawings she left behind after she was caught in the crossfire when Islamic State attacked.

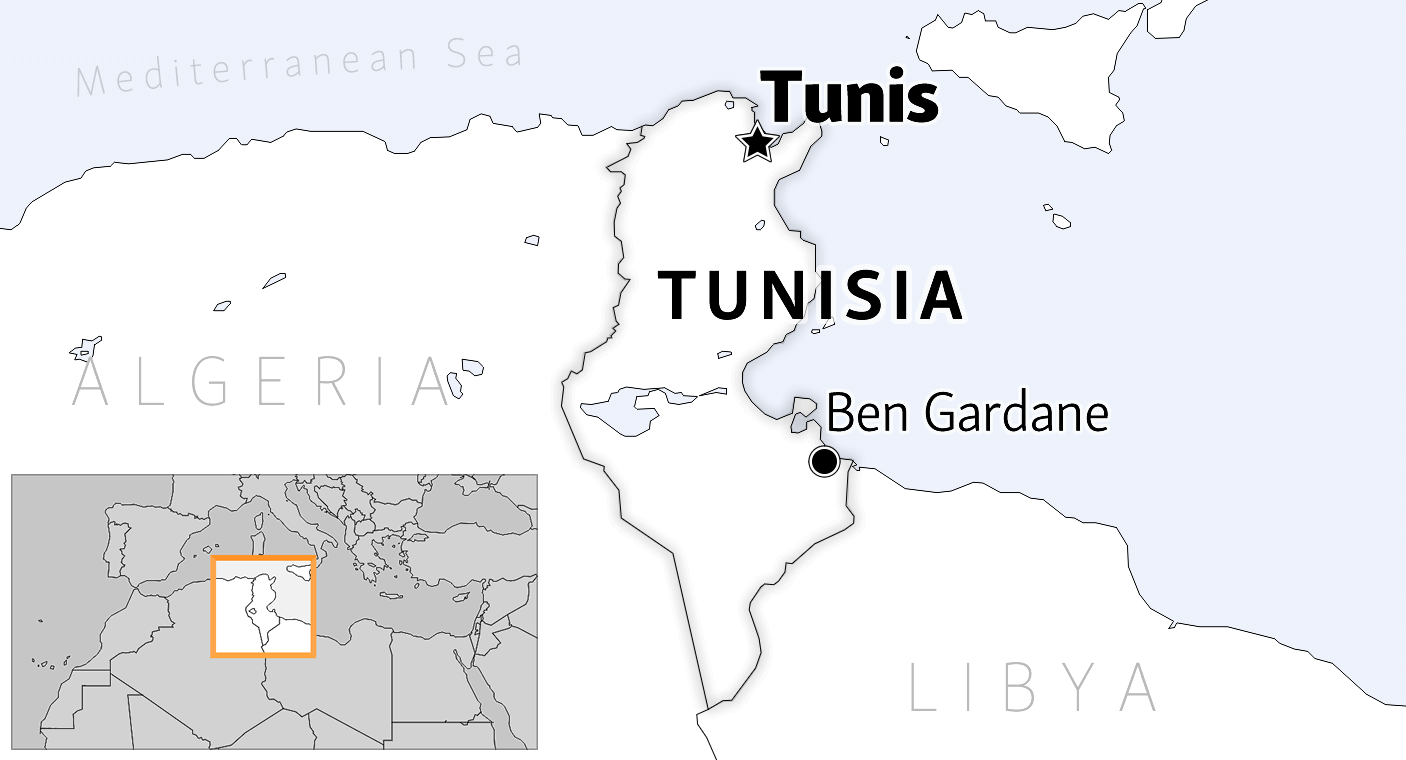

"She's not the only one who died. She is a martyr," Muaffak says, alluding to the other seven civilians killed in the March 7 assault carried out by members of the extremist group on Ben Gardane. "They are the symbol not only of Ben Gardane, but of all of Tunisia."

Residents of the southeastern desert town recall their battle with Islamic State (IS) militants with pride, but the attack was a wake-up call for Tunisia. The country is at once is the only democracy to emerge from the Arab Spring and the most prolific exporter of foreign fighters to IS and other radical groups in Syria and Iraq. At least 6,000 Tunisian fighters have joined their ranks, and about 15 percent of Tunisian recruits come from Ben Gardane, according to the Soufan Group, a firm that provides intelligence assessments to governments and organizations.

Some of them, including the Ben Gardane attackers, trained in Libya -- where vast territory, absence of government, and large stockpiles of weapons have allowed Islamic State to thrive -- and returned to pursue targets in Tunisia.

Now, as the Tunisian government works to step up security and reduce the attraction to IS, citizens are struggling with the fallout.

Sins Of The Children

Muaffak had the privilege of knowing that his 16-year-old daughter was innocent.

But Olfa Hamrouni, a single mother of five from a town in Tunisia's northeast, met news of a deadly mass shooting at a tourist resort near Sousse in June of last year with trepidation, knowing that her two eldest daughters had slipped away to join IS in Libya.

"I could breathe easier once I saw the list of attackers," Hamrouni says. Seeing one of her daughters on it, especially the younger Rahma, would have been heartrending. "I hoped and prayed that -- if God loved me -- if she carried out an attack it would be abroad -- in Libya or Syria, not in Tunisia. Because I would suffer a lot if I saw my daughter cut to pieces after the attack."

"I hoped and prayed that if she carried out an attack it would be abroad."

Olfa Hamrouni, speaking about her teenage daughter Rahma, an IS recruit

Hamrouni says that four years ago, she was grateful to see Rahma, now 17, and Ghofran, 18, become regulars at an Islamic proselytization tent near their home. They transformed from rebellious teenagers into pious Muslims, wearing black veils and urging their two younger sisters to drop out of school and follow them.

But gradually, Hamrouni realized she was losing her grip on her daughters. In July 2014, Hamrouni crossed into Libya with her children to look for work as a housekeeper. First Ghofran disappeared and joined IS. Hamrouni says she returned to Tunisia and turned Rahma in to police, but she was released and rejoined her sister in Libya. Recently, the two women were captured in Libya by anti-IS forces; Hamrouni says they are able to speak on the phone frequently thanks to a generous guard.

Hamrouni is open about her children's recruitment, and keeps Tunisian newspaper clippings featuring photographs she sent of her daughters clutching automatic weapons. Now she wants to find the recruiters who radicalized her children, and she is keeping a close eye on her other two daughters and son at their modest house in Mornag, a 45-minute drive southeast of Tunis.

"People think they are protecting their daughters by keeping this secret," Hamrouni says. "But it's the opposite. Through my experience I change the minds of lots of others."

She is an exception. Many Tunisian parents of IS fighters are quiet about their children's actions for fear of inviting police scrutiny.

One man says he was a senior member of the Tunisian intelligence services, and learned from a nameless caller that his son had died fighting for IS in Latakia, Syria, in 2014. The father speaks on condition of anonymity for fear of losing his job, and casts furtive glances up and down a busy Tunis road for possible acquaintances while he talks.

His son first traveled to Istanbul before crossing into Syria. He called home once a month, using a different phone number each time. The father is baffled that he was unable to stop his son before he left Tunisia. Now he hopes to find his body. He sums up his situation bitterly: "A man works in the secret services against terrorism, and in the end finds his son is in IS."

He is not alone. Most recently, a senior Tunisian military officer was killed in the deadly June 28 terrorist attack at Istanbul's Ataturk airport. Brigadier-General Fathi Bayoudh, a doctor at a military hospital, had reportedly traveled to Turkey to retrieve his son from IS.