As the Soviet Union adjusted to life without Stalin, the Manhoffs took their travels to the ends of the U.S.S.R.

By Mike Eckel, Wojtek Grojec, and Amos Chapple

Planes, Trains, And Avtomobili

When the Soviet Union opened a number of restricted areas to visitors in 1953, U.S. Army Major Martin Manhoff and his wife, Jan, took full advantage of the thaw that began in the wake of Stalin's death in March. They traveled widely, documenting the sights, sounds, and smells of areas of the country that had seldom — if ever — been visited by Americans.

On May 13, the Manhoffs set off on their first big adventure: a two-week journey into the heart of the country by way of the Trans-Siberian Railway. They were joined on the trip by two of Martin's colleagues from the U.S. Embassy's military attaché office.

As she did throughout her time in the Soviet Union, Jan recorded her observations in letters to friends and relatives. In an eight-page letter, she documented the group's often monotonous journey aboard a 10-car train featuring a diner, disagreeable odors, and a highly annoying radio.

As in all Soviet trains, this one was wired for receiving Radio Moscow continually, and this they did.... There are only two positions of tone control on Soviet loudspeakers, on and off. On, means as loudly as possible and that was the way which we traveled.... We did, whenever no one else was in the walkway, turn the goddamn thing off, but the two little men who were in charge of our car would come along sooner than later and grumblingly turn it on.

Jan Manhoff, undated letter

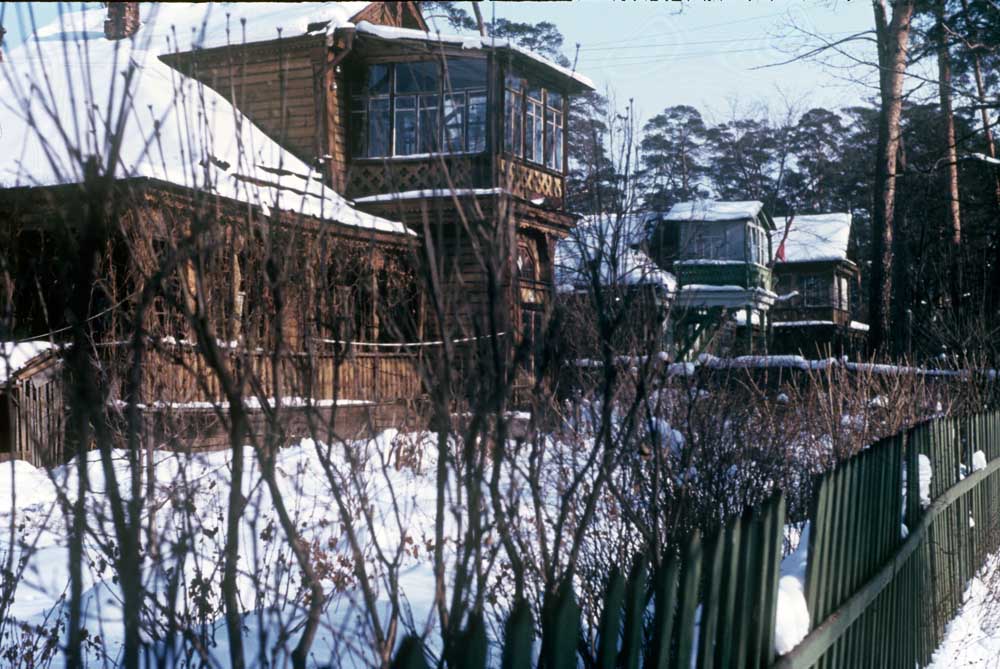

Martin shot stunning color photographs and 16 mm film as they traveled eastward for five straight days. Jan, meanwhile, took note of vast open fields and stands of birch trees, the "worn mountains" and evergreens of the Urals region, and the return to "the old flat routine" as they made their way to the heart of Siberia. Martin captured many more images on film when they finally reached Achinsk, in Siberia's Krasnoyarsky krai, and their end destination of Abakan, another 11-hour train ride to the south.

Tap/click any image to view the gallery full-screen.

Jan described the amazed looks on people's faces in Achinsk as the four Americans tried to find food and lodging and arrange tickets to Abakan. "Of course, we hadn't done any of this without attracting the attention of 99 percent of the people," she writes. "The other 1 percent couldn't look, they were lying dead drunk on the ground or any corner that would hold them."

Coming at a time when the Soviet Union was still virtually closed off from the world, the Manhoffs' trip attracted the attention of U.S. media. In one clipping, The New York Times stated that "Americans have never traveled to this remote area before."

There were signs that the Soviet authorities took notice of the Manhoffs' travels as well. During a visit to a restaurant in Achinsk, Jan noted that the manager "looked a little closely at us, but was nothing but polite." The group ate and drank and listened as "a young, tall, Siberian lad dressed in an ex-military suit and black boots came in and started playing a piano accordion ... to everyone's pleasure." The Americans bought him a beer.

"Then, it happened," Jan writes. "The manager, the man who had hung up our coats, walked in and told everyone that the cafe was closed. Everyone, with a great deal of chatter, wondered why, and many 'pochomoos' ('why') were voiced."

The accordion player made the best of the situation, playing a Russian march as the Americans left. But the incident left Jan curious: "Was it done because of us? Had we tipped the waitress too much, shouldn't we have bought the music[ian] a bottle of beer. Was it just because it was us? We'll never know."

Upon their arrival in Abakan, the travelers were taken aback by their accommodations.

Their hotel's public toilets, which were nothing more than holes in the wooden floor, drew euphemistic descriptions.

"It was before these last two doors I began holding my breath, and only sheer stubbornness kept me from breathing," she writes. "Early in the morning just after the cleaning woman had scraped things off a bit, it wasn't so bad. But late in the evening when others besides the hotel people used it, it was a little difficult finding a foot hold to maneuver over the wooden hole."

The mass of humanity which we saw at each stopping on the trip, and in Achinsk where we actually got off the train, and here in Abakan again, is staggering. People are bundled in rags, carrying bundles wrapped in rags, carrying bundles their own size wrapped in rags, it is difficult telling where bundle and human meet.

There is no extra of anything. Living for the majority of the people we saw on this whole trip is their greatest problem. There wasn't the glimmer of civilization. There was no pride, no purpose.... They chew hunks of bread and fall dead asleep waiting. They are dirty and they stink. There is no running water, they can't keep sanitary.

Jan Manhoff, undated letter

The Manhoffs would take more trips together that year and the next. They traveled to Murmansk, the Arctic Sea port that was home to the Soviet Northern Fleet, and from there by train to Arkhangelsk. They visited Kyiv, the capital of what was then known as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Martin Manhoff traveled extensively in the Soviet Union from 1952-54, often with his wife, Jan, and always with his camera. One cross-country trip he took with fellow U.S. military officers on the Trans-Siberian Railway ( ) attracted the Kremlin's attention. shows areas visited that are pictured in the Manhoff Archives. shows areas visited but not photographed.

*Note: At the time of the Manhoffs' visit, in 1953, Crimea was part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

In October, they flew to the Crimean Peninsula. The only way to travel from the Crimean capital to any other part of the peninsula was by car, so they drove from Simferopol to Bakhchysaray, Alupka, and then on to the famed resort of Yalta, the famed resort that hosted the 1945 conference where Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin decided Europe's postwar fate. The two were joined by another U.S. military attaché: Lieutenant Colonel Howard Felchlin.

In a letter dated November 4, 1953, Jan likened the Black Sea coast to that of Italy's, and suggests how foreign it felt — even to a Westerner who had become accustomed to living in Moscow.

"It was surprising to see Russian writing everywhere, and be reminded that it belonged to them, because without the people and the language, one could imagine that [w]e were in another country," she writes.

Everywhere, as always, everyone was very nice to us, treated us like guests in their own house, and I think they mite have done that if their government would allow it. They were very curious about us in the Ukraine...

Jan Manhoff, November 4, 1953

The following year, in March 1954, Martin traveled with three other attachés — including Felchlin — across the entire country to the city of Khabarovsk, on the Chinese border. Jan did not accompany them.

Tap/click any image to view the gallery full-screen.

Their journey appears to have been closely monitored. On March 25, Trud — the voice of the powerful umbrella organization for Soviet trade unions — printed a letter to the editor by a man identified as the conductor for Train No. 4, Moscow to Vladivostok. The letter complained that the Americans were taking notes as they passed several towns.

"We...were surprised at the impudence with which the several representatives of the capitalist world conducted their espionage work in our country," the letter reads.

The letter included a copy of a handwritten note, in English, that mentions various infrastructure along the route, including bridges and factories. The paper claimed it belonged to the Americans and was found in their train compartment. It also printed their names and military ranks.

On March 26, The New York Times wrote in a front-page story that the Trud article amounted to an open accusation by Soviet authorities that the four were spying.

The Seattle Times, drawing on American wire-service reports, also reported on the accusations, and quoted Martin Manhoff's mother as denying them, and saying he was scheduled to complete his assignment in Moscow in June.

"I hope he gets out," Manhoff's mother is quoted by the newspaper as saying. "I'll feel a lot better when he's home."

Nothing immediately came of the public accusations printed by Trud. Martin remained posted to Moscow for two more months, during which time he and Jan managed a trip to Kyiv.

On June 1, carrying two tickets for Train No. 30 from Moscow to Helsinki, the Manhoffs left the Soviet Union for good.